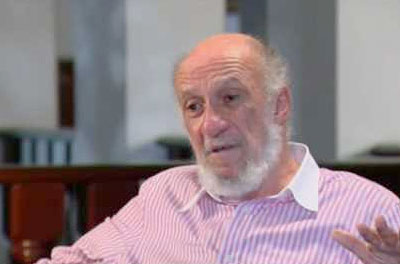

Jonathan Cook is an award winning British Journalist who has lived in Nazareth since 2001.

Jonathan Cook is an award winning British Journalist who has lived in Nazareth since 2001.

From his unique perspective on the ground, he has written three books on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

This is his latest column that appeared in Al-Jazeera August 16, 2013  and re-posted here with his permission. He does not get much exposure in the Western news media, but he should.

and re-posted here with his permission. He does not get much exposure in the Western news media, but he should.

Nazareth, Israel – Israel’s secretive arms trade is booming as never before, according to the latest export figures. But it is also coming under mounting scrutiny as some analysts argue that Israel has grown dependent on exploiting the suffering of Palestinians for military and economic gain.

A new documentary, called The Lab, has led the way in turning the spotlight on Israel’s arms industry. It claims that four million Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza have  become little more than guinea pigs in military experiments designed to enrich a new elite of arms dealers and former generals.

become little more than guinea pigs in military experiments designed to enrich a new elite of arms dealers and former generals.

The film’s release this month in the United States follows news that Israeli sales of weapons and military systems hit a record high last year of $7.5bn, up from $5.8bn the previous year. A decade ago, Israeli exports were worth less than $2bn.

Israel is now ranked as one of the world’s largest arms exporters – a considerable achievement for a country smaller than New York.

Yotam Feldman, director of The Lab and a former journalist with Israel’s Haaretz newspaper, says Israel has turned the occupied territories into a laboratory for refining, testing and showcasing its weapons systems.

His argument is supported by other analysts who have examined Israel’s military industries.

Neve Gordon, a politics professor at Ben Gurion University, said: “You only have to read the brochures published by the arms industry in Israel. It’s all in there. What they are selling is Israel’s ‘experience’ and expertise gained from the occupation and its conflicts with its neighbours.”

| Inside Story – The shift in global arms trade |

Another analyst, Jeff Halper, who is writing a book on Israel’s role in the international homeland security industry, has gone further. He argues that Israel’s success at selling its know-how to powerful states means it has grown ever more averse to returning the occupied territories to the Palestinians in a peace agreement.

Another analyst, Jeff Halper, who is writing a book on Israel’s role in the international homeland security industry, has gone further. He argues that Israel’s success at selling its know-how to powerful states means it has grown ever more averse to returning the occupied territories to the Palestinians in a peace agreement.

“The occupied territiories are crucial as a laboratory not just in terms of Israel’s internal security, but because they have allowed Israel to become pivotal to the global homeland security industry.

“Other states need Israel’s expertise, and that ensures its place at the table with the big players. It gives Israel international influence way out of keeping with its size. In turn, the hegemonic states exert no real pressure on Israel to give up the occupied territories because of their mutually reinforcing interests.”

Suggestions that Israel is exploiting the occupied territories for economic and military gain come at a sensitive moment for Israel, as it returns this week to long-stalled negotiations with the Palestinians. The commitment of Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu to the talks has already been widely questioned.

Booming arms sales

Israel’s growing success at marketing its military wares to overseas buyers was highlighted in June when defence analysts Jane’s ranked Israel in sixth place for arms exports, ahead of China and Italy, both major weapons producers.

However, Israel’s own figures, which include additional covert trade, place it in fourth place ahead of Britain and Germany, and surpassed only by the United States, Russia and France.

Shemaya Avieli, the head of Sibat, the Israeli defence ministry’s agency promoting arms exports, said at a press conference last month that the record figure had been a surprise given the “very significant economic  challenge” posed by the worldwide economic downturn.

challenge” posed by the worldwide economic downturn.

| The [Israeli] defence minister doesn’t only deal with wars, he also makes sure the defence industry is busy selling goods. |

The arms-related trade is reported to account for somewhere between one-tenth and one-fifth of Israel’s exports. The main buyers are Asian countries, especially India, Europe, the US, Canada, Australia and Latin America.

The importance of the arms trade to Israel can be gauged by a simple mathematical calculation. Last year Israel earned nearly $1,000 from the arms trade per head of population – several times the per capita income the US derives from military sales.

Israel’s reliance on the arms industry was underscored in June when a local court forced officials to publish data revealing that some 6,800 Israelis are actively engaged in exporting arms.

Separately, Ehud Barak, the defence minister in the previous Israeli government, has revealed that 150,000 Israeli households – or about one in 10 people in the country – depend economically on its military industries.

These disclosures aside, Israel has been loath to lift the shroud of secrecy that envelopes much of its arms trade. In recent court hearings it has argued that further revelations would harm “national security and foreign relations”.

‘People like to buy things that have been tested’

Feldman’s film – which won an award at DocAviv, Israel’s documentary Oscars – shows arms dealers, army commanders and government ministers speaking frankly about the way the trade has become the engine of Israel’s economic success during the global recession.

Leo Gleser, who specialises in developing new weapons markets in Latin America, observes: “The [Israeli] defence minister doesn’t only deal with wars, he also makes sure the defence industry is busy selling goods.”

The Lab suggests that arms sales have been steadily rising since 2002, when Israel reversed its withdrawals from Palestinian territory initiated by the Oslo accords. The Israeli army reinvaded the West Bank and Gaza in an operation known as Defensive Shield.

The Lab suggests that arms sales have been steadily rising since 2002, when Israel reversed its withdrawals from Palestinian territory initiated by the Oslo accords. The Israeli army reinvaded the West Bank and Gaza in an operation known as Defensive Shield.

There’s a lot of hypocrisy: they condemn you politically, while they ask you what your trick is, you Israelis, for turning blood into money.

In parallel, many retired army officers moved into the new high-tech field. There they found a chance to test their security ideas, including developing systems for long-term surveillance, control and subjugation of “enemy” populations.

The biggest surge in the arms trade followed Operation Cast Lead, Israel’s month-long attack on Gaza in winter 2008-09 that provoked international condemnation. More  than 1,400 Palestinians were killed, as well as 13 Israelis. Sales that year reached $6bn for the first time.

than 1,400 Palestinians were killed, as well as 13 Israelis. Sales that year reached $6bn for the first time.

Benjamin Ben Eliezer, a former defence minister turned industry minister, attributes Israel’s success to the fact that “people like to buy things that have been tested. If Israel sells weapons, they have been tested, tried out. We can say we’ve used this 10 years, 15 years.”

Nonetheless, The Lab‘s argument has proved controversial with some security experts. Shlomo Bron, a former air force general who now works at the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University, rejected the film’s premise.

“It may be true that in practice the military uses the occupied territories as a laboratory, but that is just an unfortunate effect of our conflict with the Palestinians. And we sell to other countries only because Israel itself is too small a market.”

The film highlights the kind of innovations for which Israel has been feted by overseas security services. It pioneered the airborne drones that are now at the heart of the US programme of extra-judicial executions in the  Middle East.

Middle East.

Israel hopes to repeat that success with missile interception systems such as Iron Dome, which was much on display when rockets were fired out of Gaza during last year’s Operation Pillar of Cloud.

Futuristic weapons

The Lab also underscores the Israeli arms industry’s success in developing futuristic weapons, such as the gun that shoots around corners. The bullet-bending firearm caught Hollywood’s attention, with Angelina Jolie wielding it – and effectively marketing it – in the 2008 film Wanted.

Halper believes that Israel has made itself useful to powerful states not just in terms of developing weapons systems, but by becoming particularly successful at what he terms “niche-filling”.

“The United States, for example, knows better than anyone how to attack other countries, as it did with Iraq and Afghanistan. Israel can’t teach it much on that score. But the US doesn’t have much idea what to do after the attack, how to pacify the population. That is where Israel steps in and offers its expertise.”

This point is underscored in The Lab. Its unlikeliest stars are former Israeli officers turned academics, whose theories have helped to guide the Israeli army and hi-tech companies in developing new military techniques and strategies much sought-after by foreign militaries.

This point is underscored in The Lab. Its unlikeliest stars are former Israeli officers turned academics, whose theories have helped to guide the Israeli army and hi-tech companies in developing new military techniques and strategies much sought-after by foreign militaries.

Shimon Naveh, a military philosopher, is shown pacing through a mock Arab village that provided the canvas on which he devised a new theory of urban warfare to deal with the second Palestinian intifada, after it erupted in late 2000.

| |

| UN states fail to reach arms trade treaty |

In the run-up to an attack in 2002 on Nablus’ casbah, much feared by the Israeli army for its labyrinthine layout, he suggested that the soldiers move not through the alleyways, where they would be easy targets, but unseen through the buildings, knocking holes through the walls that separated the houses.

In the run-up to an attack in 2002 on Nablus’ casbah, much feared by the Israeli army for its labyrinthine layout, he suggested that the soldiers move not through the alleyways, where they would be easy targets, but unseen through the buildings, knocking holes through the walls that separated the houses.

Naveh’s idea became the key to crushing Palestinian armed resistance, exposing the only places – in the heart of overcrowded cities and refugee camps – where Palestinian fighters could still find sanctuary from Israeli surveillance.

Another expert, Yitzhak Ben Israel, a former general who is now a professor at Tel Aviv University, helped to develop a mathematical formula for the Israeli military that predicts the likely success of assassination programmes to end organised resistance.

Ben Israel’s calculus proved to the army that a Palestinian cell planning an attack could be destroyed with high probability by “neutralising” as few as one-fifth of its fighters.

This merging of theory, hardware and repeated “testing” in the field has had armies, police forces and the homeland security industries lining up to buy Israeli know-how, Feldman argues. The lessons learned in Gaza and the West Bank have also had applications in Afghanistan and Iraq.

This merging of theory, hardware and repeated “testing” in the field has had armies, police forces and the homeland security industries lining up to buy Israeli know-how, Feldman argues. The lessons learned in Gaza and the West Bank have also had applications in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Yoav Galant, the head of the Israeli army’s southern command during Cast Lead, however, criticises the double standards of the international community.

“While certain countries in Europe or Asia condemned us for attacking civilians, they sent their officers here, and I briefed generals from 10 countries,” he says. “There’s a lot of hypocrisy: they condemn you politically, while they ask you what your trick is, you Israelis, for turning blood into money.”

A spokesman for the Israeli defence ministry called the arguments made in The Lab “flawed and illogical”.

“Our success in defence industries reflects the fact that Israel has had to be resourceful and creative faced with an existential threat for more than 60 years as well as a series of wars with the Arab world.”

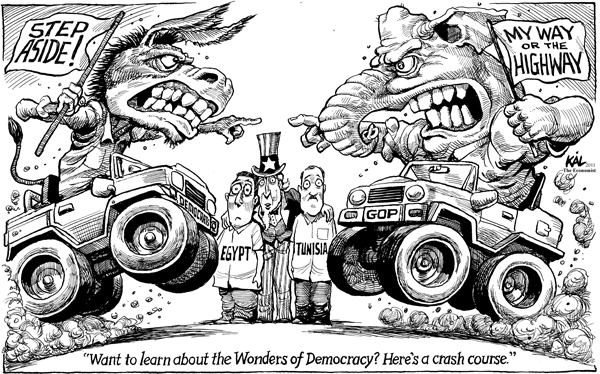

My interest in this report calls me to question such a fundamental conflict of interest. Examining the reality in this world, the American-Israeli Axis proliferates more  Weapons of War, Death, Destruction and Intimidation to the world than all other Nations combined. These two Nations claim to behave with the highest morality, integrity and standards of Almighty God.

Weapons of War, Death, Destruction and Intimidation to the world than all other Nations combined. These two Nations claim to behave with the highest morality, integrity and standards of Almighty God.

When, O LORD, will you fulfill the words of your Servant, The Prophet?

the word that Isaiah the son of Amoz saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem.

And it shall come to pass in the last days, that the mountain of the LORD’s house shall be established in the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills; and ALL NATIONS shall flow unto it.

And many people shall go and say, Come, and let us go up to the mountain of the LORD, to the house of the God of Jacob; and he will teach us of his ways, and we will walk in his paths: for out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of the LORD from Jerusalem.

And he shall judge among the nations, and shall rebuke many people: and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.

O house of Jacob, come, and let us walk in the light of the LORD.

Therefore you have forsaken your people the house of Jacob, because they be replenished from the east, and are soothsayers like the Philistines, and they please themselves in the children of strangers.

Their land also is full of silver and gold, neither is there any end of their treasures; their land is also full of horses, neither is there any end of their chariots:

Their land also is full of idols; they worship the work of their own hands, that which their own fingers have made:

And the mean man bows down, and the great man humbles himself: therefore forgive them not.

Enter into the rock, and hide yourself in the dust, for fear of the LORD, and for the glory of his majesty.

The lofty looks of man shall be humbled, and the haughtiness of men shall be bowed down, and the LORD alone shall be exalted in that day.

For the day of the LORD of hosts shall be upon every one that is proud and lofty, and upon every one that is lifted up; and he shall be brought low:

And upon all the cedars of Lebanon, that are high and lifted up, and upon all the oaks of Bashan,

And upon all the high mountains, and upon all the hills that are lifted up,

And upon every high tower, and upon every fenced wall,

And upon all the ships of Tarshish, and upon all pleasant pictures.

And the loftiness of man shall be bowed down, and the haughtiness of men shall be made low: and the LORD alone shall be exalted in that day.

And the idols he shall utterly abolish.

And they shall go into the holes of the rocks, and into the caves of the earth, for fear of the LORD, and for the glory of his majesty, when he arises to shake terribly the earth.

In that day a man shall cast his idols of silver, and his idols of gold, which they made each one for himself to worship, to the moles and to the bats;

To go into the clefts of the rocks, and into the tops of the ragged rocks, for fear of the LORD, and for the glory of his majesty, when he arises to shake terribly the earth.

Cease ye from man, whose breath is in his nostrils: for wherein is he to be accounted of?

For more information supporting the premise of Jonathan Cook’s article, follow the link below.

Reading Jeff Halper’s ‘War Against the People: Israel, the Palestinians and Global Pacification’

October 23, 2017

Israel maintains robust arms trade with rogue regimes

Israel’s booming secretive arms trade

Al-Jazeera – 16 August 2013

Israel’s secretive arms trade is booming as never before, according to the latest export figures. But it is also coming under mounting scrutiny as some analysts argue that Israel has grown dependent on exploiting the suffering of Palestinians for military and economic gain.

A new documentary, called The Lab, has led the way in turning the spotlight on Israel’s arms industry. It claims that four million Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza have become little more than guinea pigs in military experiments designed to enrich a new elite of arms dealers and former generals.

The film’s release this month in the United States follows news that Israeli sales of weapons and military systems hit a record high last year of $7.5bn, up from $5.8bn the previous year. A decade ago, Israeli exports were worth less than $2bn.

Israel is now ranked as one of the world’s largest arms exporters – a considerable achievement for a country smaller than New York.

Yotam Feldman, director of The Lab and a former journalist with Israel’s Haaretz newspaper, says Israel has turned the occupied territories into a laboratory for refining, testing and showcasing its weapons systems.

His argument is supported by other analysts who have examined Israel’s military industries.

Neve Gordon, a politics professor at Ben Gurion University, said: “You only have to read the brochures published by the arms industry in Israel. It’s all in there. What they are selling is Israel’s ‘experience’ and expertise gained from the occupation and its conflicts with its neighbours.”

Another analyst, Jeff Halper, who is writing a book on Israel’s role in the international homeland security industry, has gone further. He argues that Israel’s success at selling its know-how to powerful states means it has grown ever more averse to returning the occupied territories to the Palestinians in a peace agreement.

“The occupied territiories are crucial as a laboratory not just in terms of Israel’s internal security, but because they have allowed Israel to become pivotal to the global homeland security industry.

“Other states need Israel’s expertise, and that ensures its place at the table with the big players. It gives Israel international influence way out of keeping with its size. In turn, the hegemonic states exert no real pressure on Israel to give up the occupied territories because of their mutually reinforcing interests.”

Suggestions that Israel is exploiting the occupied territories for economic and military gain come at a sensitive moment for Israel, as it returns this week to long-stalled negotiations with the Palestinians. The commitment of Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu to the talks has already been widely questioned.

Booming arms sales

Israel’s growing success at marketing its military wares to overseas buyers was highlighted in June when defence analysts Jane’s ranked Israel in sixth place for arms exports, ahead of China and Italy, both major weapons producers.

However, Israel’s own figures, which include additional covert trade, place it in fourth place ahead of Britain and Germany, and surpassed only by the United States, Russia and France.

Shemaya Avieli, the head of Sibat, the Israeli defence ministry’s agency promoting arms exports, said at a press conference last month that the record figure had been a surprise given the “very significant economic challenge” posed by the worldwide economic downturn.

The arms-related trade is reported to account for somewhere between one-tenth and one-fifth of Israel’s exports. The main buyers are Asian countries, especially India, Europe, the US, Canada, Australia and Latin America.

The importance of the arms trade to Israel can be gauged by a simple mathematical calculation. Last year Israel earned nearly $1,000 from the arms trade per head of population – several times the per capita income the US derives from military sales.

Israel’s reliance on the arms industry was underscored in June when a local court forced officials to publish data revealing that some 6,800 Israelis are actively engaged in exporting arms.

Separately, Ehud Barak, the defence minister in the previous Israeli government, has revealed that 150,000 Israeli households – or about one in 10 people in the country – depend economically on its military industries.

These disclosures aside, Israel has been loath to lift the shroud of secrecy that envelopes much of its arms trade. In recent court hearings it has argued that further revelations would harm “national security and foreign relations”.

‘People like to buy things that have been tested’

Feldman’s film – which won an award at DocAviv, Israel’s documentary Oscars – shows arms dealers, army commanders and government ministers speaking frankly about the way the trade has become the engine of Israel’s economic success during the global recession.

Leo Gleser, who specialises in developing new weapons markets in Latin America, observes: “The [Israeli] defence minister doesn’t only deal with wars, he also makes sure the defence industry is busy selling goods.”

The Lab suggests that arms sales have been steadily rising since 2002, when Israel reversed its withdrawals from Palestinian territory initiated by the Oslo accords. The Israeli army reinvaded the West Bank and Gaza in an operation known as Defensive Shield.

In parallel, many retired army officers moved into the new high-tech field. There they found a chance to test their security ideas, including developing systems for long-term surveillance, control and subjugation of “enemy” populations.

The biggest surge in the arms trade followed Operation Cast Lead, Israel’s month-long attack on Gaza in winter 2008-09 that provoked international condemnation. More than 1,400 Palestinians were killed, as well as 13 Israelis. Sales that year reached $6bn for the first time.

Benjamin Ben Eliezer, a former defence minister turned industry minister, attributes Israel’s success to the fact that “people like to buy things that have been tested. If Israel sells weapons, they have been tested, tried out. We can say we’ve used this 10 years, 15 years.”

Nonetheless, The Lab’s argument has proved controversial with some security experts. Shlomo Bron, a former air force general who now works at the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University, rejected the film’s premise.

“It may be true that in practice the military uses the occupied territories as a laboratory, but that is just an unfortunate effect of our conflict with the Palestinians. And we sell to other countries only because Israel itself is too small a market.”

The film highlights the kind of innovations for which Israel has been feted by overseas security services. It pioneered the airborne drones that are now at the heart of the US programme of extra-judicial executions in the Middle East.

Israel hopes to repeat that success with missile interception systems such as Iron Dome, which was much on display when rockets were fired out of Gaza during last year’s Operation Pillar of Cloud.

Futuristic weapons

The Lab also underscores the Israeli arms industry’s success in developing futuristic weapons, such as the gun that shoots around corners. The bullet-bending firearm caught Hollywood’s attention, with Angelina Jolie wielding it – and effectively marketing it – in the 2008 film Wanted.

Halper believes that Israel has made itself useful to powerful states not just in terms of developing weapons systems, but by becoming particularly successful at what he terms “niche-filling”.

“The United States, for example, knows better than anyone how to attack other countries, as it did with Iraq and Afghanistan. Israel can’t teach it much on that score. But the US doesn’t have much idea what to do after the attack, how to pacify the population. That is where Israel steps in and offers its expertise.”

This point is underscored in The Lab. Its unlikeliest stars are former Israeli officers turned academics, whose theories have helped to guide the Israeli army and hi-tech companies in developing new military techniques and strategies much sought-after by foreign militaries.

Shimon Naveh, a military philosopher, is shown pacing through a mock Arab village that provided the canvas on which he devised a new theory of urban warfare to deal with the second Palestinian intifada, after it erupted in late 2000.

In the run-up to an attack in 2002 on Nablus’ casbah, much feared by the Israeli army for its labyrinthine layout, he suggested that the soldiers move not through the alleyways, where they would be easy targets, but unseen through the buildings, knocking holes through the walls that separated the houses.

Naveh’s idea became the key to crushing Palestinian armed resistance, exposing the only places – in the heart of overcrowded cities and refugee camps – where Palestinian fighters could still find sanctuary from Israeli surveillance.

Another expert, Yitzhak Ben Israel, a former general who is now a professor at Tel Aviv University, helped to develop a mathematical formula for the Israeli military that predicts the likely success of assassination programmes to end organised resistance.

Ben Israel’s calculus proved to the army that a Palestinian cell planning an attack could be destroyed with high probability by “neutralising” as few as one-fifth of its fighters.

This merging of theory, hardware and repeated “testing” in the field has had armies, police forces and the homeland security industries lining up to buy Israeli know-how, Feldman argues. The lessons learned in Gaza and the West Bank have also had applications in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Yoav Galant, the head of the Israeli army’s southern command during Cast Lead, however, criticises the double standards of the international community.

“While certain countries in Europe or Asia condemned us for attacking civilians, they sent their officers here, and I briefed generals from 10 countries,” he says. “There’s a lot of hypocrisy: they condemn you politically, while they ask you what your trick is, you Israelis, for turning blood into money.”

A spokesman for the Israeli defence ministry called the arguments made in The Lab “flawed and illogical”.

“Our success in defence industries reflects the fact that Israel has had to be resourceful and creative faced with an existential threat for more than 60 years as well as a series of wars with the Arab world.”

– See more at: http://www.jonathan-cook.net/2013-08-18/israels-booming-secretive-arms-trade/#sthash.nm2M6NtF.dpuf

Israel’s booming secretive arms trade

Al-Jazeera – 16 August 2013

Israel’s secretive arms trade is booming as never before, according to the latest export figures. But it is also coming under mounting scrutiny as some analysts argue that Israel has grown dependent on exploiting the suffering of Palestinians for military and economic gain.

A new documentary, called The Lab, has led the way in turning the spotlight on Israel’s arms industry. It claims that four million Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza have become little more than guinea pigs in military experiments designed to enrich a new elite of arms dealers and former generals.

The film’s release this month in the United States follows news that Israeli sales of weapons and military systems hit a record high last year of $7.5bn, up from $5.8bn the previous year. A decade ago, Israeli exports were worth less than $2bn.

Israel is now ranked as one of the world’s largest arms exporters – a considerable achievement for a country smaller than New York.

Yotam Feldman, director of The Lab and a former journalist with Israel’s Haaretz newspaper, says Israel has turned the occupied territories into a laboratory for refining, testing and showcasing its weapons systems.

His argument is supported by other analysts who have examined Israel’s military industries.

Neve Gordon, a politics professor at Ben Gurion University, said: “You only have to read the brochures published by the arms industry in Israel. It’s all in there. What they are selling is Israel’s ‘experience’ and expertise gained from the occupation and its conflicts with its neighbours.”

Another analyst, Jeff Halper, who is writing a book on Israel’s role in the international homeland security industry, has gone further. He argues that Israel’s success at selling its know-how to powerful states means it has grown ever more averse to returning the occupied territories to the Palestinians in a peace agreement.

“The occupied territiories are crucial as a laboratory not just in terms of Israel’s internal security, but because they have allowed Israel to become pivotal to the global homeland security industry.

“Other states need Israel’s expertise, and that ensures its place at the table with the big players. It gives Israel international influence way out of keeping with its size. In turn, the hegemonic states exert no real pressure on Israel to give up the occupied territories because of their mutually reinforcing interests.”

Suggestions that Israel is exploiting the occupied territories for economic and military gain come at a sensitive moment for Israel, as it returns this week to long-stalled negotiations with the Palestinians. The commitment of Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu to the talks has already been widely questioned.

Booming arms sales

Israel’s growing success at marketing its military wares to overseas buyers was highlighted in June when defence analysts Jane’s ranked Israel in sixth place for arms exports, ahead of China and Italy, both major weapons producers.

However, Israel’s own figures, which include additional covert trade, place it in fourth place ahead of Britain and Germany, and surpassed only by the United States, Russia and France.

Shemaya Avieli, the head of Sibat, the Israeli defence ministry’s agency promoting arms exports, said at a press conference last month that the record figure had been a surprise given the “very significant economic challenge” posed by the worldwide economic downturn.

The arms-related trade is reported to account for somewhere between one-tenth and one-fifth of Israel’s exports. The main buyers are Asian countries, especially India, Europe, the US, Canada, Australia and Latin America.

The importance of the arms trade to Israel can be gauged by a simple mathematical calculation. Last year Israel earned nearly $1,000 from the arms trade per head of population – several times the per capita income the US derives from military sales.

Israel’s reliance on the arms industry was underscored in June when a local court forced officials to publish data revealing that some 6,800 Israelis are actively engaged in exporting arms.

Separately, Ehud Barak, the defence minister in the previous Israeli government, has revealed that 150,000 Israeli households – or about one in 10 people in the country – depend economically on its military industries.

These disclosures aside, Israel has been loath to lift the shroud of secrecy that envelopes much of its arms trade. In recent court hearings it has argued that further revelations would harm “national security and foreign relations”.

‘People like to buy things that have been tested’

Feldman’s film – which won an award at DocAviv, Israel’s documentary Oscars – shows arms dealers, army commanders and government ministers speaking frankly about the way the trade has become the engine of Israel’s economic success during the global recession.

Leo Gleser, who specialises in developing new weapons markets in Latin America, observes: “The [Israeli] defence minister doesn’t only deal with wars, he also makes sure the defence industry is busy selling goods.”

The Lab suggests that arms sales have been steadily rising since 2002, when Israel reversed its withdrawals from Palestinian territory initiated by the Oslo accords. The Israeli army reinvaded the West Bank and Gaza in an operation known as Defensive Shield.

In parallel, many retired army officers moved into the new high-tech field. There they found a chance to test their security ideas, including developing systems for long-term surveillance, control and subjugation of “enemy” populations.

The biggest surge in the arms trade followed Operation Cast Lead, Israel’s month-long attack on Gaza in winter 2008-09 that provoked international condemnation. More than 1,400 Palestinians were killed, as well as 13 Israelis. Sales that year reached $6bn for the first time.

Benjamin Ben Eliezer, a former defence minister turned industry minister, attributes Israel’s success to the fact that “people like to buy things that have been tested. If Israel sells weapons, they have been tested, tried out. We can say we’ve used this 10 years, 15 years.”

Nonetheless, The Lab’s argument has proved controversial with some security experts. Shlomo Bron, a former air force general who now works at the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University, rejected the film’s premise.

“It may be true that in practice the military uses the occupied territories as a laboratory, but that is just an unfortunate effect of our conflict with the Palestinians. And we sell to other countries only because Israel itself is too small a market.”

The film highlights the kind of innovations for which Israel has been feted by overseas security services. It pioneered the airborne drones that are now at the heart of the US programme of extra-judicial executions in the Middle East.

Israel hopes to repeat that success with missile interception systems such as Iron Dome, which was much on display when rockets were fired out of Gaza during last year’s Operation Pillar of Cloud.

Futuristic weapons

The Lab also underscores the Israeli arms industry’s success in developing futuristic weapons, such as the gun that shoots around corners. The bullet-bending firearm caught Hollywood’s attention, with Angelina Jolie wielding it – and effectively marketing it – in the 2008 film Wanted.

Halper believes that Israel has made itself useful to powerful states not just in terms of developing weapons systems, but by becoming particularly successful at what he terms “niche-filling”.

“The United States, for example, knows better than anyone how to attack other countries, as it did with Iraq and Afghanistan. Israel can’t teach it much on that score. But the US doesn’t have much idea what to do after the attack, how to pacify the population. That is where Israel steps in and offers its expertise.”

This point is underscored in The Lab. Its unlikeliest stars are former Israeli officers turned academics, whose theories have helped to guide the Israeli army and hi-tech companies in developing new military techniques and strategies much sought-after by foreign militaries.

Shimon Naveh, a military philosopher, is shown pacing through a mock Arab village that provided the canvas on which he devised a new theory of urban warfare to deal with the second Palestinian intifada, after it erupted in late 2000.

In the run-up to an attack in 2002 on Nablus’ casbah, much feared by the Israeli army for its labyrinthine layout, he suggested that the soldiers move not through the alleyways, where they would be easy targets, but unseen through the buildings, knocking holes through the walls that separated the houses.

Naveh’s idea became the key to crushing Palestinian armed resistance, exposing the only places – in the heart of overcrowded cities and refugee camps – where Palestinian fighters could still find sanctuary from Israeli surveillance.

Another expert, Yitzhak Ben Israel, a former general who is now a professor at Tel Aviv University, helped to develop a mathematical formula for the Israeli military that predicts the likely success of assassination programmes to end organised resistance.

Ben Israel’s calculus proved to the army that a Palestinian cell planning an attack could be destroyed with high probability by “neutralising” as few as one-fifth of its fighters.

This merging of theory, hardware and repeated “testing” in the field has had armies, police forces and the homeland security industries lining up to buy Israeli know-how, Feldman argues. The lessons learned in Gaza and the West Bank have also had applications in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Yoav Galant, the head of the Israeli army’s southern command during Cast Lead, however, criticises the double standards of the international community.

“While certain countries in Europe or Asia condemned us for attacking civilians, they sent their officers here, and I briefed generals from 10 countries,” he says. “There’s a lot of hypocrisy: they condemn you politically, while they ask you what your trick is, you Israelis, for turning blood into money.”

A spokesman for the Israeli defence ministry called the arguments made in The Lab “flawed and illogical”.

“Our success in defence industries reflects the fact that Israel has had to be resourceful and creative faced with an existential threat for more than 60 years as well as a series of wars with the Arab world.”

– See more at: http://www.jonathan-cook.net/2013-08-18/israels-booming-secretive-arms-trade/#sthash.nm2M6NtF.dpuf

Jonathan Cook is an award-winning British journalist based in Nazareth, Israel, since 2001.

He is the author of three books on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict:

- Blood and Religion: The Unmasking of the Jewish State (2006)

- Israel and the Clash of Civilisations: Iraq, Iran and the Plan to Remake the Middle East (2008)

- Disappearing Palestine: Israel’s Experiments in Human Despair (2008)

– See more at: http://www.jonathan-cook.net/about/#sthash.d27xWoeB.dpuf

Jonathan Cook is an award-winning British journalist based in Nazareth, Israel, since 2001.

He is the author of three books on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict:

- Blood and Religion: The Unmasking of the Jewish State (2006)

- Israel and the Clash of Civilisations: Iraq, Iran and the Plan to Remake the Middle East (2008)

- Disappearing Palestine: Israel’s Experiments in Human Despair (2008)

– See more at: http://www.jonathan-cook.net/about/#sthash.d27xWoeB.dpuf